A cikin hankalin daɗi da ke nuna a tashar muhimman jihohin tattalin arzikin masana'antu, yadda ake amfani da tattalin arziki na Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM) na gaba ta shafi shi wajen inganta hankalin daɗi da kuma ƙarin haduwar harmonics. A nan, tattalin arziki na PWM na mafi tsawo yana ƙara ƙwalitas na output waveform da kuma yana ƙare system harmonics tare da ƙara frequency na carrier, wanda ya haɗa da inganci da inverter. Saboda haka, bayan gwamnati da tsafta a cikin amfani da tattalin arziki na PWM na mafi tsawo ya zama batun da fiye a cikin tashar tattalin arziki na inverter.

1. Fittar Tarihi da Kula-kula na Teknikoki na PWM na Mafi Tsawo

Tattalin arziki na PWM shine fittar tarihi mai ban sha'awa a cikin electrical control systems na inverter don kawo voltage da frequency. Yana samun pulse sequences tare da ƙara reference signals da carrier signals, sannan yana amfani da wannan pulse sequences don kawo switching states na power devices, wanda yake da shi a yi kawo precise control ga power supply zuwa load. A cikin inverter control, duty cycle DD na PWM zai iya tabbatar da amplitude VrefVref na reference wave da amplitude VtriVtri na carrier wave kamar haka:

Modulation ratio mm ana ƙirƙira a matsayin ratio na amplitude na reference wave zuwa amplitude na carrier wave. Yana taimakawa effective value da kuma harmonic characteristics na output voltage. Expression na wannan ratio shine:

Carrier frequency fcfc ana nufin frequency na triangular wave wanda ake amfani don samun signal na PWM. Value na wannan yana taimakawa dynamic response speed na system da kuma distribution na output harmonics. Frequency ratio NN ana ƙirƙira a matsayin ratio na carrier frequency zuwa reference wave frequency, expressed as:

ida f1 shine reference wave frequency. High-frequency PWM technology generally refers to PWM control techniques with a carrier frequency exceeding 10 kHz. In modern inverters, with continuous improvements in power device performance, carrier frequencies have reached 20 kHz or even higher. By increasing the carrier frequency, the output harmonic components are shifted to higher frequency ranges, facilitating subsequent filtering and effectively reducing motor noise and vibration.

Experiments show that increasing the carrier frequency from 5 kHz to 20 kHz can reduce motor noise by 12–15 dB and lower temperature rise by 5–8 °C. As the carrier frequency increases, the PWM output waveform more closely approximates an ideal sine wave, and the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) is significantly reduced. At a carrier frequency of 20 kHz, the THD of the inverter output voltage drops to approximately 5%, which is considerably better than the 8%–12% typical of low-frequency PWM techniques. Furthermore, high-frequency PWM offers advantages such as faster dynamic response and higher control accuracy.

2. Key Challenges in Implementing High-Frequency PWM and Their Solutions

2.1 High Switching Losses and Mitigation Methods

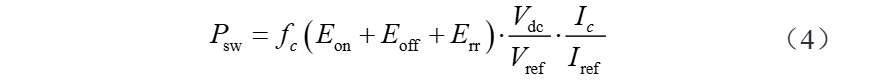

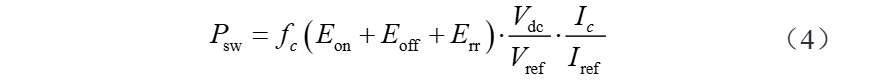

The most prominent issue with high-frequency PWM technology is the sharp increase in switching losses. Since the switching losses of power devices are proportional to the switching frequency, high-frequency operation leads to reduced system efficiency and increased demands on thermal management. The switching loss PswPsw of a single Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistor (IGBT) module can be modeled as follows:

where Eon and Eoff are the turn-on and turn-off energy losses, respectively; ErrErr is the reverse recovery energy; VdcVdc is the actual DC bus voltage; Vref is the reference voltage; Ic is the actual current; and IrefIref is the reference current.

To suppress switching losses, the following measures can be adopted:

First, use advanced power devices such as Silicon Carbide Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors (SiC MOSFETs), which offer superior switching characteristics compared to conventional IGBTs;

Second, optimize the gate driver circuit design by employing dual-slope drive techniques to dynamically adjust the gate resistance during switching transitions, thereby balancing switching speed and electromagnetic interference (EMI);

Finally, implement soft-switching techniques, such as zero-voltage switching (ZVS) or zero-current switching (ZCS) topologies, to significantly reduce switching losses.

2.2 Dead-Time Effect and Compensation Techniques

Under high-frequency PWM operation, although the absolute dead-time remains constant, its proportion relative to the switching period increases, making the dead-time effect more pronounced. This can lead to output voltage distortion, degraded low-speed performance, and increased torque ripple. To effectively mitigate these issues, dead-time compensation algorithms are employed, expressed as:

3 FPGA-Based Implementation Scheme for High-Frequency PWM Technology

3.1 System Architecture Design

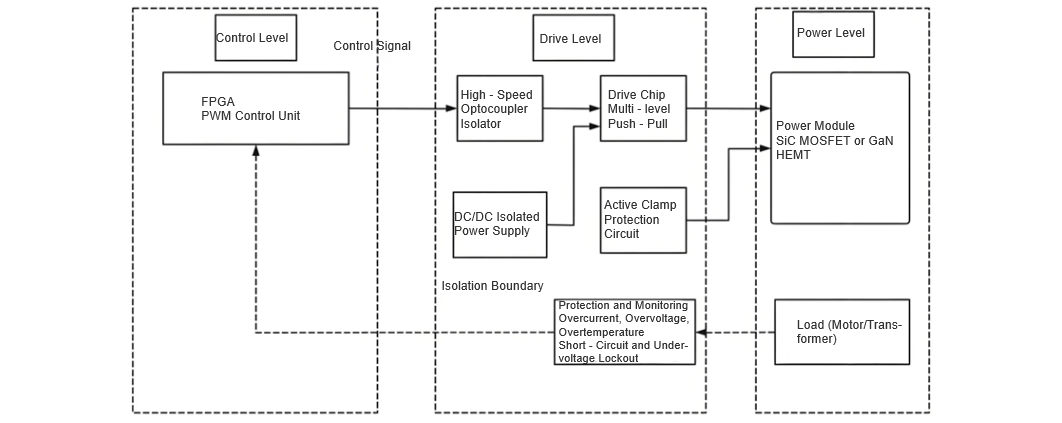

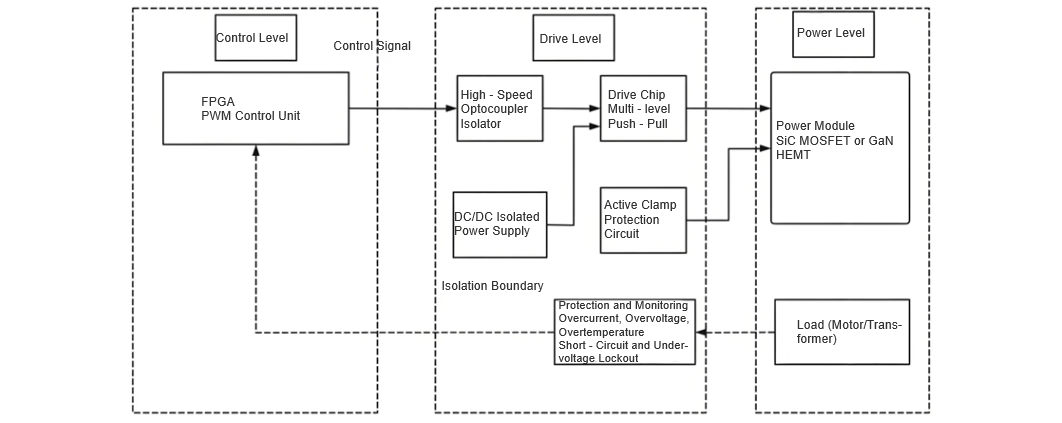

High-frequency PWM control imposes higher demands on the real-time performance and control precision of computing platforms. Traditional Digital Signal Processors (DSPs) often face limitations such as insufficient computational power and significant interrupt latency when implementing high-frequency PWM. In contrast, Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are better suited for such applications due to their parallel processing capabilities and hardware-level implementation flexibility.

The overall architecture of the FPGA-based high-frequency PWM control system consists of four core modules: the main control unit, the PWM generation unit, the feedback signal processing unit, and the protection unit. Specifically:

Main Control Unit: Executes closed-loop control algorithms such as speed, current, and position loops;

PWM Generation Unit: Responsible for generating high-precision PWM waveforms and managing dead-time control;

Feedback Signal Processing Unit: Handles the acquisition and preprocessing of signals such as current, voltage, and position;

Protection Unit: Detects and responds to faults such as overcurrent, overvoltage, and overtemperature to ensure system safety.

The system adopts a modular design, with functional modules interconnected via standardized interfaces. Internally, the FPGA employs a dual-clock-domain architecture: control algorithms operate in a lower-frequency clock domain to reduce resource consumption, while the PWM generation module runs in a high-frequency clock domain to ensure precise timing and high resolution.

3.2 Optimization and Implementation of PWM Control Algorithm

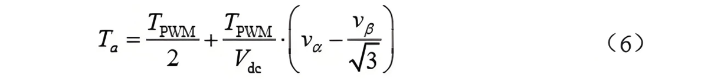

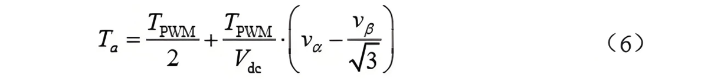

To achieve high-performance high-frequency PWM control, the conventional Space Vector Pulse Width Modulation (SVPWM) algorithm is optimized by introducing an improved PWM control algorithm, expressed as:

where TaTa is the conduction time of the upper leg of Phase A; vαvα and vβvβ are the components of the reference voltage in the α-βα-β coordinate system. This algorithm is implemented in the FPGA using a pipelined architecture, transforming complex trigonometric computations into simple linear operations. This significantly reduces computational latency and enables single-cycle execution. To optimize dead-time control, an adaptive dead-time compensation strategy is adopted.

3.3 System Performance Testing and Analysis

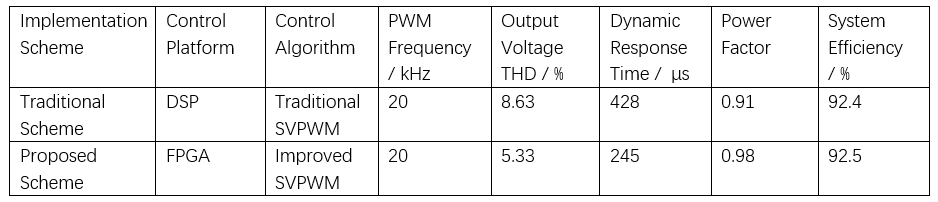

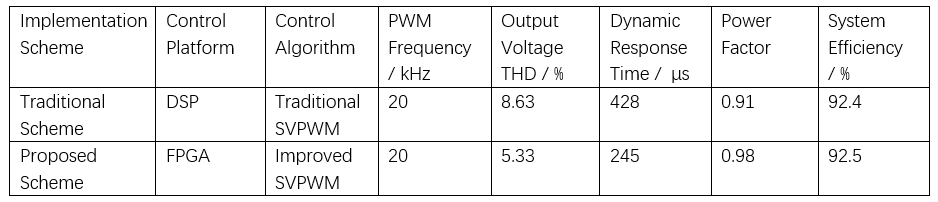

To evaluate the superiority of the proposed high-frequency PWM implementation scheme (hereinafter referred to as the "proposed scheme"), it is compared with a conventional DSP-based implementation (hereinafter referred to as the "conventional scheme"). The test platform is built on a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA and a TMS320F28379D DSP, using identical power-level circuit topologies and power modules (1200 V/50 A SiC MOSFET). Performance metrics include output voltage Total Harmonic Distortion (THD), dynamic response time, power factor, and system efficiency. Each test is repeated three times, with results averaged to ensure reliability.

As shown in Table 1, the proposed scheme demonstrates significant advantages over the conventional scheme across most metrics: output voltage THD is reduced from 8.63% to 5.33%, a 38.2% improvement; dynamic response time decreases from 428 μs to 245 μs, a 42.5% reduction; and power factor increases from 0.91 to 0.98. Although the system efficiency improves by only 0.1%, this marginal gain is still meaningful given the already high baseline efficiency exceeding 92%.

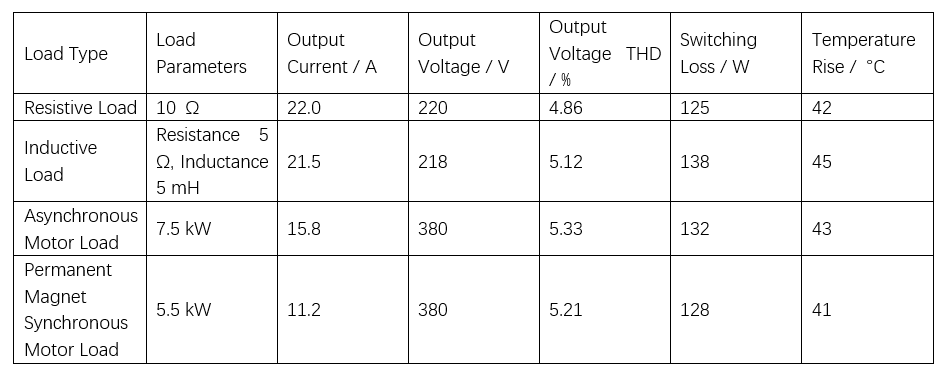

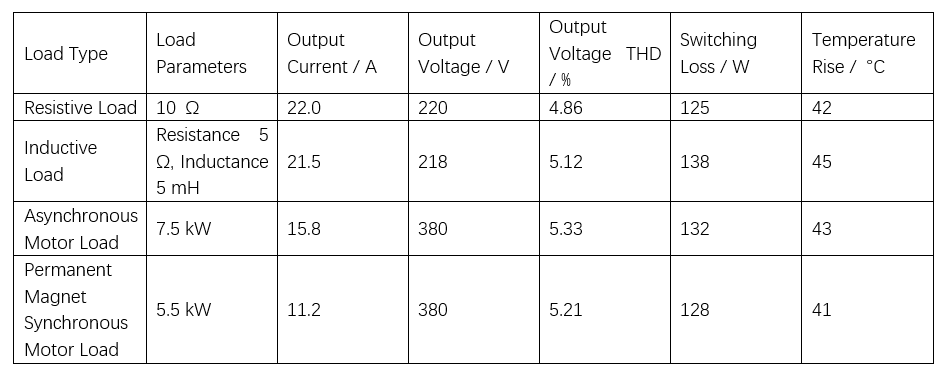

The feasibility of the proposed scheme under varying load conditions is further tested, with results presented in Table 2. The tests cover resistive, inductive, and motor loads. The results show that the proposed scheme maintains stable performance across all load types: the variation in output voltage THD is only 0.47%, demonstrating excellent robustness of the control algorithm; switching losses are maintained between 125 W and 138 W, with a fluctuation of just 10.4%, indicating effective power management; and temperature rise is kept within 41–45 °C, confirming superior thermal stability.

4 Conclusion

High-frequency PWM technology is a key enabler for enhancing inverter performance, yet its implementation in electrical control systems faces multiple technical challenges. This paper addresses critical issues such as high-frequency switching losses, dead-time effects, and driver circuit design by proposing systematic solutions and presenting an FPGA-based implementation framework.

The proposed scheme offers high precision, low latency, and strong real-time performance, effectively improving both dynamic response and steady-state accuracy. The research provides solid technical support for high-performance inverter control and holds broad application potential in fields such as industrial automation, renewable energy generation, and electric vehicles.