Railway power systems primarily consist of automatic block signaling lines, through-feeder power lines, railway substations and distribution stations, and incoming power supply lines. They provide electricity to critical railway operations—including signaling, communications, rolling stock systems, station passenger handling, and maintenance facilities. As an integral part of the national power grid, railway power systems exhibit distinct characteristics of both electrical power engineering and railway infrastructure.

Strengthening research into neutral grounding methods for conventional-speed railway power systems—and comprehensively considering these methods during design, construction, and operation—is highly significant for enhancing the safety and reliability of railway power supply.

1. Overview of Neutral Grounding Methods in Railway Power Systems

The neutral grounding method in railway power systems typically refers to the grounding configuration of transformers—a form of functional (working) grounding closely tied to voltage level, single-phase ground-fault current, overvoltage levels, and relay protection schemes. It is a complex technical issue that can be broadly categorized into:

Non-solidly grounded systems: including ungrounded, arc-suppression coil (Petersen coil) grounded, and high-resistance grounded systems;

Solidly grounded systems: including direct grounding and low-resistance grounding.

Power supplied from the national grid to railways universally adopts an ungrounded neutral configuration. Feeder circuits from railway substations and distribution stations are typically tapped directly from the secondary busbar (located after the incoming power bus but before the voltage regulator), thus also employing an ungrounded neutral system. For through-feeder lines, the grounding method of the voltage-regulating transformer may be selected based on actual needs.

Unlike high-speed railway power systems—which commonly use low-resistance grounding—conventional-speed railway systems predominantly employ ungrounded neutral configurations. While this approach offers certain advantages, evolving safety standards and ongoing technical upgrades warrant re-evaluation of grounding strategies in today’s operational context.

2. Advantages and Limitations of Ungrounded Neutral Systems

According to the Railway Power Design Code (TB 10008–2015), the configuration of through-feeder lines should be determined based on power supply reliability and project-specific conditions, using either overhead-cable hybrid lines or fully underground cable lines.

Due to budget constraints and technical feasibility, most operational conventional-speed railway through-feeder lines currently rely primarily on overhead conductors or overhead-dominant hybrid configurations. Consequently, their neutral grounding schemes typically adopt insulated-neutral (ungrounded) or small-current grounding systems. Per Article 69 of the Railway Power Management Rules, single-phase ground faults in such systems must be addressed promptly, with allowable fault operation time generally not exceeding 2 hours.

Operational data from a specific railway bureau segment between January and October 2023 recorded 152 power trips, of which 15 were equipment-related failures (2 attributable to internal responsibility, 13 to external factors). Notably, environmental hazards—particularly vegetation encroachment—pose the primary threat to overhead line stability. In one incident, tree branches intruded into the clearance zone, causing a partial phase-to-ground connection on a side conductor. The fault was identified and resolved within the 2-hour window, preventing any impact on train operations and avoiding cascading failures. This demonstrates that, under existing technical conditions, ungrounded neutral systems offer practical benefits.

However, cable lines present different challenges. Compared to overhead lines, power cables have lower insulation margins and limited overvoltage tolerance. During a single-phase ground fault in an ungrounded system, the healthy-phase voltages rise above normal phase-to-ground levels—potentially reaching line-to-line voltage—increasing the risk of multi-point insulation breakdown in non-fault phases. Moreover, capacitive ground-fault currents in cable systems are relatively large, leading to rapid insulation degradation at the fault point and a high likelihood of evolving into phase-to-phase short circuits.

Because cables are typically installed via buried, conduit, or tray methods, fault location is difficult. Combined with constraints in cable jointing techniques, repair logistics, and railway operational windows, such faults often cannot be resolved quickly. In practice, cable failures are predominantly due to permanent insulation breakdown—organic insulation materials cannot self-recover. In an ungrounded system, the lack of immediate tripping allows prolonged fault currents, causing severe insulation damage, expanding the fault zone, and potentially triggering secondary issues such as power screen alarms or even "red-band" signal failures that disrupt train services—sometimes resulting in prolonged outages and significant safety or public relations risks.

3. Selection of Neutral Grounding Methods for Conventional-Speed Railway Power Systems

Selecting the appropriate neutral grounding method is critical for stable railway power operation. The core challenge lies in balancing:

Minimizing unnecessary tripping caused by external disturbances,

Ensuring uninterrupted power to critical loads,

Enabling effective fault protection,

Controlling fault propagation, and

Maintaining electrical and insulation integrity of healthy equipment during faults.

Per the Railway Power Design Code (TB 10008–2015), for 10(20) kV through-feeder lines supplied via voltage regulators, the following grounding guidelines apply:

If the single-phase ground-fault capacitive current ≤ 10 A, an ungrounded system shall be used.

If the current ≤ 150 A, either low-resistance grounding or arc-suppression coil grounding may be adopted; if > 150 A, low-resistance grounding is recommended.

Fully cable-based lines should preferably use low-resistance grounding.

For low-resistance grounding, the grounding resistor should be selected to yield a single-phase ground current of 200–400 A, with instantaneous tripping upon fault detection.

In contrast, the High-Speed Railway Design Code (TB 10621–2014) permits ungrounded neutral systems when ground-fault capacitive current ≤ 30 A, with compensation provided via a neutral-grounded reactor.

Based on calculations from standard railway power engineering handbooks, the maximum allowable cable lengths for common aluminum-core cables (70 mm² and 95 mm² cross-sections) corresponding to single-phase ground-fault capacitive currents of 10 A, 30 A, 60 A, 100 A, and 150 A are summarized in Table 1. These values can guide the selection of an appropriate grounding method based on actual cable length.

| Serial No. |

Single-phase grounding capacitive current of three-core cable (A) |

Average capacitive current of three-core 70 mm² cross-section cable (A/km) |

Corresponding cable length (km) |

Average capacitive current of three-core 95 mm² cross-section cable (A/km) |

Corresponding cable length (km) |

| 1 |

10

|

0.9 |

11.11 |

1.0

|

10.00 |

| 2 |

30 |

0.9 |

33.33 |

1.0 |

30.00 |

| 3 |

60 |

0.9 |

66.67

|

1.0 |

60.00 |

| 4 |

100 |

0.9 |

111.11 |

1.0 |

100.00 |

| 5 |

150 |

0.9 |

166.67 |

1.0 |

150.00 |

Grounding via the neutral point enables rapid fault clearance. Zero-sequence protection can operate within 0.2–2.0 seconds to isolate the fault, reducing the probability of secondary permanent electrical incidents and protecting the insulation reliability and service life of power equipment.

4. Comparison of Common Neutral Grounding Methods

4.1 Ungrounded Neutral System

The ungrounded neutral method offers the advantage of continuous power supply for 1–2 hours during single-phase ground faults in lines dominated by overhead conductors. However, in cable-dominated lines, this method tends to cause fault escalation.

4.2 Neutral Grounding via Arc-Suppression Coil

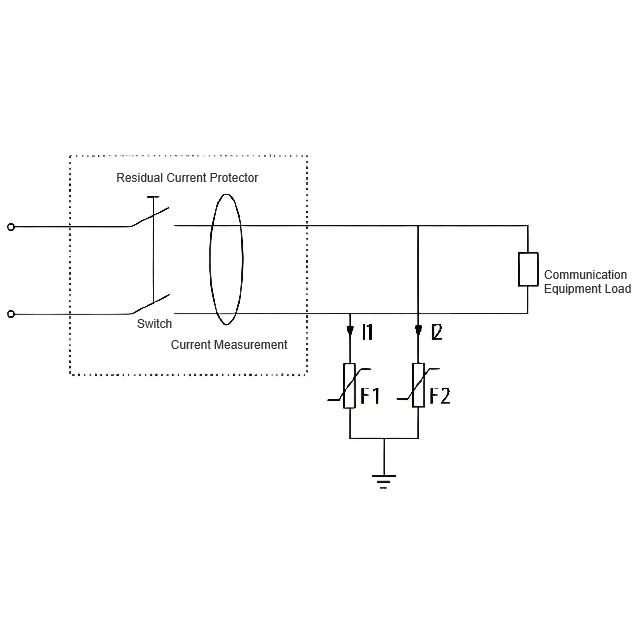

Compared with the ungrounded neutral system, this method uses the inductive current of the arc-suppression coil to compensate for capacitive current, reducing the ground-fault current to a level that can self-extinguish, thereby minimizing arc-induced overvoltages. It also allows 1–2 hours of continuous operation during single-phase ground faults and prevents single-phase faults from developing into phase-to-phase faults. However, this method imposes higher requirements on ground-fault protection, cannot identify the faulty line, is prone to resonance, and cannot effectively discharge residual charges on the line.

4.3 Neutral Grounding via Low Resistance

In cable-dominated lines, the low-resistance grounding method effectively controls arc-ground overvoltages during single-phase ground faults, suppresses system resonant overvoltages, provides good current-limiting and voltage-reducing effects, and offers relatively high zero-sequence overcurrent protection performance, facilitating timely fault elimination. However, this method has limitations, especially in overhead line sections: increased tripping frequency affects power system operation, weakens power supply capability, and increases equipment maintenance difficulty to some extent.

5. Discussion on Neutral Grounding Methods for Railway Power Systems

(1) Enhance the utilization of automatic tracking arc-suppression coil devices. This approach has the advantage of automatically eliminating transient ground faults in the power system, thereby reducing the number of trips. When a fault alarm signal is issued, the automatic tracking arc-suppression coil generates a corresponding compensating current, enabling re-compensation of the power line. This reduces the occurrence of short-circuit faults among the three phases and ensures system stability and safety. Meanwhile, since the arc-suppression device has a specific arc-extinguishing critical value, if the ground-fault current is smaller than this critical value, the voltage recovery speed increases under the action of the arc-suppression device, helping extinguish the arc reliably and reducing the likelihood of arc re-ignition, thereby decreasing power incidents and effectively supporting reliable neutral grounding operation.

(2) During the renovation of existing conventional-speed through-feeder and automatic block signaling lines, if cable lines—after replacing overhead lines—account for a significant proportion, it is recommended to consider centralized or distributed compensation using box-type reactors to compensate for inductive reactive power under normal capacitive current conditions. According to the calculation results in Table 2, the operating capacitance values are 0.22 μF/km for 70 mm² aluminum-core cable and 0.24 μF/km for 95 mm² aluminum-core cable. Simultaneously, adaptability modifications to distribution rooms should be considered, and the neutral grounding methods of voltage regulators in distribution rooms on both sides should be adjusted accordingly based on calculated data.

| Serial No. |

Steady-state capacitive current of three-core cable (A) |

Average steady-state capacitive current of 70 mm² three-core cable (A/km) |

Corresponding cable length (km) |

Average steady-state capacitive current of 95 mm² three-core cable (A/km) |

Corresponding cable length (km) |

Capacitive reactive power of cable line (kvar) |

Inductive reactive power required to compensate 75% of steady-state (kvar) |

| 1 |

3

|

0.4 |

7.5 |

0.44 |

6.82 |

51.96 |

38.97 |

| 2 |

5 |

0.4 |

12.5 |

0.44 |

11.36 |

86.6 |

64.95 |

| 3 |

10 |

0.4 |

25

|

0.44 |

22.73 |

173.2 |

129.9 |

| 4 |

15 |

0.4 |

37.5

|

0.44 |

34.09 |

259.3 |

194.85 |

| 5 |

30

|

0.4 |

75 |

0.44 |

68.18 |

519.6 |

389.7 |

In extreme cases, if the system is ungrounded and single-core cables—complying with high-speed railway standards—are used, a single-phase ground fault will not be cleared within the allowable 2-hour window. This causes continuous thermal damage to the cable. Moreover, after a single-core cable is damaged, its impact on adjacent phases is relatively weak, further exacerbating the situation by failing to trigger protective tripping, which can easily lead to systemic failures.

6. Conclusion

In conventional-speed railway power systems, the selection of the neutral grounding method directly affects the safety and stability of system operation. An inappropriate choice of neutral grounding scheme can easily result in secondary faults and cascading incidents. Through calculation and comparative analysis, a comprehensive and rational selection of the neutral grounding method is of great significance for effectively clearing faults, protecting equipment insulation, ensuring reliable traction power supply, and enhancing both personnel and train operation safety.